Living with type 1 presents numerous challenges, stresses, and fears. The list includes hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, complications, early death, injections, burnout, body weight, being judged, pregnancy, money, data, wearables, and insertables.

Whew … That’s an exhaustive list!

While I’ve come to terms with most, several are still a work in progress. Experience helps. Below is what’s worked for me in overcoming diabetes fears and the power and benefits of struggle, fear, and mindset.

Hypoglycemia

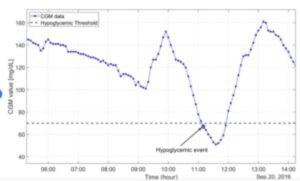

Hypoglycemia usually occurs when blood sugar goes below normal levels. Below is a graph of blood sugar dropping below 70 mg/dl. Blood sugars below that level can result in symptoms including confusion, sweating, feeling hungry, tingling lips, shaking, anxiety, irritation, and double vision.

I lived with this fear daily for the first four decades of my diabetes. One semester in junior high school, my schedule included a late lunch. So late in the morning, NPH insulin started working well before lunch. Many days, I perspired in class, became confused, and hoped the teacher wouldn’t call on me. It was all I could do to get to the cafeteria after class.

Approximately ten times a year in my twenties and thirties (1980s and 90s), I either failed to wake up due to extremely low blood sugar or woke up severely confused. Before faster and more pure insulin, lows could come without warning and be extreme. Some type 1s don’t appreciate this scene in the 1989 movie Steel Magnolias, but my friends and family will attest that this behavior was not an exaggeration during those times:

Fortunately, for me, extreme hypoglycemia subsided with these moves:

- Using fast-acting insulin (Humalog)

- Stopped using cloudy long-acting insulin (NPH)

- Changing my nutrition to 40-30-30. (40% of calories from carbohydrates, 30% protein, 30% healthy fats.) The benefit? Protein and fats slow down the digestion of carbs and delay their absorption into the blood.

Since then, I have experienced moderate lows that I usually anticipate, feel, and treat. And my A1Cs are consistently in the 5.5 – 6.5% range. When on a CGM, the time in range is 90%+.

Although I have mixed thoughts on the effectiveness of closed-loop technology, I have found the suspend before low algorithms in the Loop software, Medtronic, and Tandem devices to be effective for reducing hypoglycemia. They do a terrific job moderating basal rates to keep blood sugars from going low.

Although I don’t fear extreme hypoglycemia as much as I used to, it’s still a concern. And I’m not alone … 30% of adults living with type 1 have a fear of hypoglycemia.

Hyperglycemia

Another spectrum of blood sugar management is blood sugars above the normal range of 80-180. And there’s much to fear about elevated blood sugars over a long period as they can result in complications. The good news? Unlike low blood sugars, temporarily elevated blood sugars don’t immediately impact our quality of life. Even more, some fear of long-term hyperglycemia motivates maintaining blood sugars within range. That’s how it works for me.

Complications

Eyes, kidneys, heart, gastroparesis, oral health, nerves, body amputations. That’s an exhaustive list of the breakdowns that can occur in our bodies due to type 1 diabetes. It turns out that elevated blood glucose levels over a long period damage blood vessels. Poor vessels won’t transport blood to all body parts, resulting in damaged nerves and organs.

Being diagnosed at age 3, I didn’t think about complications much during my childhood (I’m sure my parents did). Growing up and getting through school was challenging enough!

It was in my 20s that endocrinologists drilled in me (with many fear tactics) that elevated blood sugars over the years could lead to one or more of the above complications. It worked … these were deal-breakers for me. About that time (the early-1980s), blood glucose meters arrived on the scene, and I became obsessed with keeping my blood sugars as close to normal as possible.

Today, tech advances like continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), pumps, and algorithms connecting them help keep blood sugars within range. Despite these improvements, complications from diabetes still occur.

How have I dealt with the threat of complications?

- To respect the possibility that they may happen (mine include background retinopathy, frozen shoulder, and Dupuytren contracture).

- If and when they do, lean into friends & family while working with the best medical professionals.

- To do my part in the areas I control (I’m a bit obsessive with blood sugar data, diet, and exercise).

- To embrace new technology and meds.

- To strive for an A1C in a non-diabetic range below 6.0. (Yep, it is attainable.)

Since 2005, Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston has studied people with type 1 diabetes for over 50 years. Called the Medalist Study; here’s a link to a post about my 50-year medalist visit. During my visit, they shared that while there are no critical biological markers in the 50-year group, there are several tendencies:

- We tend to be active.

- We tend to have a positive outlook.

- We tend to have a post-high school education, with many having graduate degrees.

- On average, we drink 6 cups of coffee per day.

- We drink alcohol in moderation.

While I share the above tendencies with the larger medalist group, both nature and nurture are involved in living well with type 1.

All four of my grandparents were born around 1900 and lived well into their 80s and beyond (not bad for the hills of Appalachia and rural Missouri). My parents are still alive at age 90. And yes, diabetes was present on both sides. But to be clear, I received some very good DNA with one major exception.

As for nurture, I’ve worked my butt off to achieve good control. I’ve left no stone unturned and consider that my part in living well with type 1 for so long. After all, we only get one body … why not take the best care of it?

Simply said: Nurture your Nature!

Premature Death

This site is dedicated to my wife’s sister, Kelly, who died from diabetes complications at age 35 (she was diagnosed at age 11). She struggled with many of these challenges and others, including acceptance, insulin resistance, and diabulimia. The suffering she, her Mom and Dad, my wife, and her siblings endured was long and painful.

Through it all, Kelly set an example of courage and positivity. She was a terrific writer and wrote notes of encouragement to friends and family. After amputating both legs, she embraced setbacks and new possibilities, including prosthetic devices. She rejoiced when my wife donated a kidney.

Throughout her journey, Kelly had love from family, friends, and help from medical professionals. That was the best medicine in a life taken too early.

Needles and Injections

Living with type 1 means injecting insulin (*). Then finger sticks for a blood meter sample or the needle to insert a sensor for a continuous glucose monitor. And the longer needle involved in blood draws from a lab (I still don’t look). That’s a lot of sticks!

Early in our diagnosis, we must work through some fear of sticking ourselves. For me, it started with perfecting the technique on an orange. But my skin felt different than an orange. At some point, I pinched my skin and went for it (it wasn’t as bad as I had imagined). Eventually, it became commonplace.

It helps that today’s syringes, insulin pens, and pump infusion sets have significantly improved. Needles used to inject insulin are now short and fine. It’s a rare occasion when they hit a nerve.

Once comfortable with a needle, the number of times we stick ourselves can be overwhelming (when I was on multiple daily injections, I averaged 6-7 injections and 8-10 finger sticks a day). That’s why some use an insulin pump or a continuous glucose monitor. One stick every 2-3 days for a pump or more than a week for a CGM is an improvement.

For more on fears of needles and strategies to work them, click here: https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/features/needle-fears-and-phobia.html

(*) Mannkind has Affreza, an inhalable insulin that can be used before meals. But long-acting insulin still needs to be injected.

Burnout

Type 1 diabetes is a lifelong partner. It doesn’t take a day off. There are times when diabetes wins the day. And if that becomes a pattern, we become overwhelmed and unable to keep up with the demands of managing diabetes. That’s burnout.

It’s happened to me. There are weeks where blood sugars stay elevated and others with a will to stay below 70. And times while leading an important meeting or presentation, only to have Mr. Hypo take over. All this despite my best efforts to keep blood sugars within range.

I’ve never gotten to the point where I gave up (*), but I have been uber-frustrated. Early in adulthood, I chose to fight back. But that wasn’t always a suitable environment for others around me. While I still get frustrated, I’ve found better outlets that include exercise, mindfulness, faith, music, and sports.

Here’s a link to a concise article on managing diabetes burnout.

(*) I have known type 1s that have worn a pump and refused to bolus or press buttons.

Body Weight

Type 1 involves matching the correct amount of insulin to the carbohydrates we consume. Too much insulin, and we must eat unwanted carbs to avoid low blood sugars. It happened to me for years. This can result in more body weight.

Conversely, consistently high blood sugars, or long-term hyperglycemia, can result in ketoacidosis. When this happens, our bodies start to break down fat for energy. Toxins called ketones build up in our bloodstream and spill into our urine. It also results in weight loss.

So there you have it … Type 1 is a balancing act of the right amount of insulin, carbohydrates, exercise, and stress. For decades, I chased excess insulin with unwanted carbohydrates. It was frustrating, and I looked for better ways. I found answers by:

- understanding and nailing my insulin ratios (basal, bolus, and sensitivity)

- moving from a high carbohydrate diet to a more balanced 40-30-30 nutrition. This approach, sometimes called The Zone, has 40% of its calories from carbohydrates, 30% from protein, and 30% from fats. Protein and fat delay the absorption of carbohydrates, resulting in fewer post-prandial (after meals) blood sugar spikes. I’ve also found it easier to calculate and align insulin.

How did this influence body weight? In high school and college, I weighed 185 pounds on a 6’ frame … I was in good physical shape playing competitive sports and consistently working out. Fast forward to age 40 with a family, career demands, travel, and business dinners. My weight approached 200 pounds, and I said enough was enough. I studied and implemented the 40-30-30 nutrition, and my weight moved back to 185 pounds, where it remains today.

I’m not recommending the 40-30-30 approach for everyone … I tried several solutions, and it’s the one that worked for me. I recommend finding a nutrition solution that lets us control insulin requirements and blood sugars. The benefits include being in charge of your body weight.

Judgment

Type 1 comes with various diet, exercise, technology, and medication choices. And constant report cards of blood sugars, A1C, and time in range.

It’s easy for us to judge ourselves if we miss any of these.

My solution? Stop judging. Start comparing yourself to a standard. Performance to a standard can be moved. Judging and worrying about your actions serves no purpose. Comparing your scores to a standard does.

Once we place our sights on standards (and our means to get there), the judgment sometimes delivered by medical professionals and well-intending family members is like water on a duck’s back.

We may even help them understand more about living with diabetes!

Lesson Learned: stop judging ourselves. Instead, compare our results to standards of care. Numbers can be managed. And moved. Without judgment.

Pregnancy

We’re made to procreate (IMHO … responsibly). To create and influence the next generation. Type 1 adds a dimension to the privilege and responsibility of being pregnant.

For male and female type 1s, pregnancy comes with the risk of passing it on to future generations (*).

For females, being pregnant comes with the responsibility of managing blood sugars tightly. Gone are the days when women with type 1 were discouraged from getting pregnant … for decades, I’ve known women who have done it well (**).

(*) here are the probabilities of passing type 1 diabetes as published by the American Diabetes Association:

- If giving birth before age 25: 1 in 25

- If giving birth after 25: 1 on 100

- If you are a man with type 1: 1 in 17

- If both partners have type 1: 1 in 10-14

- If you developed type 1 before age 11: the risk is doubled

(**) My sister-in-law Katie was diagnosed at age six and had three children. Two were diagnosed with type 1 at 18 months and age 6. She felt great during each of her pregnancies.

Money

Not having funds to provide for the required staples of life = stress. For most, these are housing, clothing, food, and transportation. But having type 1 mandates insulin, the tech to deliver it, and physician appointments to obtain it.

In the U.S., a 2020 study revealed $18,817 annually for a person with type 1 and $11,002 specifically for diabetes. In 2022, billings to insurance for my diabetes care totaled $23,399 (with insurance company discounts … retail prices are higher). My cost was $2,296. That’s the power of an excellent medical insurance plan. But what about those not fortunate to have insurance?

We may opt not to buy insulin due to recent – outrageous – price increases (*). When we cannot afford the meds and tech, we sacrifice other staples like food, clothes, car maintenance, rest, and relaxation. This 2022 study reveals that 1.4 million of us – over 18% of type 1s in the U.S. – have rationed insulin due to high prices.

There have been times when my insurance didn’t cover my diabetes costs very well. What moves did I make?

- purchasing insulin from Canada. My 90-day supply of five Humalog vials cost $47.94 each versus $280 from my medical insurance plan.

- using blood meters and test strips instead of CGM transmitters and sensors.

- extending the use of pump cartridges by changing only the tail of my infusion set.

- My endocrinologist moved my appointments to bi-annual instead of quarterly (when in good control)

(*) 2023 legislation in the U.S. is curbing the patient cost of insulin. It’s about time … too many type 1s lives have been compromised because of greed in the insulin supply chain.

Data

The tools and technology available in the diabetes marketplace today provide data, insights, and a means to tighter control. It can also be overwhelming. And annoying. And consuming.

As a perfectionist and tightly wired at times (especially when my blood sugars aren’t cooperating), data presents challenges for me, primarily with ever-present CGM data. I sometimes become obsessed with blood sugar data (even when I’m in range). It consumes my attention and actions. It feels like something else is measuring me … every 5 minutes. When this happens, I get stressed.

My answer? Go back to blood meter sticks. When I do this, I feel a huge sense of relief. My wife and friends tell me I’m more relaxed. I focus on life events rather than my CGM screen.

While I understand the benefits of data, too much of it stresses me out.

Wearables & Insertables

Living with Type 1 includes choices for infusing insulin and obtaining blood sugar data. Our options include the following:

- Infusion sets for insulin pumps inserted into the tissue below our skin and stay attached to our bodies via an adhesive.

- Continuous glucose monitors with sensors inserted below our skin and transmitters that remain on our bodies.

These ‘insertables & wearables’ have the potential to create a variety of concerns:

- Detachment – infusion and CGM sites can disconnect unintentionally. I’ve had infusion set tubing get caught on various objects (door knobs!) … the results have ranged from a distracting pause to the infusion site being ripped out. While exercising on hot days, infusion sets and CGM sensors can slide off due to body sweat. When infusion sites come off, our source of insulin stops. Lost CGM data interrupts closed-loop algorithms. Both outcomes create immediate concern. My solution is easy => keep extra supplies nearby!

- Tech glitches: blocked infusion sets, bloody CGM sites, skin rashes, and bruised or infected infusion sites happen. The solution is like the first step of tech support … remove and reinstall.

- Tech settings (basal, bolus, sensitivity ratios). These are SO important, and getting these wrong results in wide swings in blood sugars, moods, and frustration. These have gotten much easier to nail with CGM data.

- Real estate issues – finding fresh skin and body locations for infusion sets and CGMs can be challenging after days and years of use … especially when underlying tissue gets scarred. Rotating helps, but to this day, I mostly avoid my hip area due because I relied on them exclusively for too long.

- Incorrect dosing (button pushes). Giving the intended amount of insulin with a syringe or insulin pen is easy. Not always so with an insulin pump screen. Tandem’s remote bolus feature is my most recent example. I was moving higher during a group cycling ride for some unknown reason. While stopped at a traffic light, I removed my phone from my jersey and input 0.5 units … or so I thought. As I headed home, I felt light-headed and dizzy. I wasn’t wearing a CGM, so I stopped a did a check with my blood meter … 43. WTF? I pulled my pump and looked at my bolus history. Aargh … I had incorrectly input five units instead of 0.5. I was fortunate to be close to home … hello kitchen pantry!

- Being different – wearables are usually visible and raise questions from others. Some of us want to keep our diabetes in the background or not talk about it and may have issues with pulling a pump out at lunch or explaining a CGM on the back of our arm. This was certainly the case for me with my first pump. I was socially conscious about wearing it and explaining it to others I didn’t know well. I now wear both proudly and believe they are badges of honor. They’ve even become a conversation opener.

- Loss of freedom & independence – these devices are attached to our bodies. That can create a sense of losing our independence. When wearing closed-loop systems, we defer some of the responsibility for managing diabetes to a machine (this is a challenging area for me). We must manage technology and our diabetes. Sometimes that results in a diabetes double whammy.

So how do we deal with the challenges, stresses, and fears of diabetes?

For my first five decades living with diabetes, I researched and responded to each of these challenges as they presented themselves. It was much work, and I often fought back when I felt overwhelmed (I’m glad I did).

But since then, I’ve found several methods that benefit my life with the Big D. These moves are more proactive and less stressful. They help all humans, but the demands of living with diabetes make these more impactful to us type 1s.

Here’s an the diabetes management strategies I’ve used to overcome diabetes fears:

Mindset

ONE. Observe … Not Engage.

When living with diabetes, it’s normal to engage directly with the above challenges. And for the first four to five decades of my life with diabetes, that’s mostly how I dealt with them. And while usually successful, it often moved me into an emotional quicksand that continued well beyond the event. My mind wondered what could happen in any of the areas.

Rather than engage, I have learned that observing the challenges creates objectivity, awareness, and better decisions. The benefits include more controlled responses, better choices, and improved wellness.

Observing (and not engaging) requires a change in mindset.

How to get there is beyond the scope of this post, but my mind was first opened when a friend asked me to buddy up on an eight-week path for learning mindfulness (*). It required commitment but was very straightforward.

Life is full of choices – and type 1 isn’t one of them – but how we respond to the fears of living with diabetes is.

(*) Here’s a link to the book “Mindfulness” by Mark Williams and Danny Penman that started my journey into mindset.

The Benefits of Struggle

Working through pain, challenges, struggles – and fears – results in learning. Facing and working on fears creates experiences that result in new knowledge, perspectives, and skills. For me, they include discipline, attention to detail, accountability, problem-solving, teamwork, and perseverance.

It can be tempting to avoid or escape our struggles. Don’t … that’s hitting the easy button. George Mumford is the mindful guru Phil Jackson used when he coached the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers. In his book The Mindful Athlete, he shares how escaping our fears (for him, it was with drugs) robs us of the stress people naturally develop. He says that the gift of desperation compels us to move forward. That happened to me as a young adult … I became too frustrated with my blood sugar roller coaster, propelling me to find a better way to live with type 1.

Embracing, facing, and working on the challenges, frustrations, and fears of your diabetes develops skills to live your best with type 1.

Want a bonus benefit? ==> These experiences make us emotionally strong and resilient for other challenges that life throws your way.

The Power and Protection of Fear

I shared writing about the fears of diabetes with my wife, Kendra, and she offered that fear can serve as a protector, identifying areas where we should be cautious. Indeed, Merriam-Webster defines fear as a strong unpleasant emotion caused by anticipation or awareness of danger.

I hadn’t considered fear a protector, but looking back, that’s how it worked for me. It guided me to identify the challenges of living with diabetes and develop solutions that help and protect me from harm. For areas that I still struggle with – data overload and self-judgment – it serves as a reminder to be attentive to those areas.

There are two sides to a coin, and thinking about fear as protection is a new paradigm for me. I also know that fear can lead to anxiety and helplessness … in those times, we gotta lean into help.

Don’t Go About It Alone

Managing diabetes is best with a team … with us type 1s as team captains. I like to distinguish between an A-Team and others.

A-Team members are our constant source of support. I keep this team to 5 or fewer members.

- Family and close friends

- Endocrinologist – this physician specializes in the endocrine system, including the pancreas and diabetes. They are also responsible for scripts and prior authorizations needed for our insulin, medical devices (pumps, infusion sets, and CGMs), and other medications. Please do your homework, talk with others, and try them out. I’ve worked with at least three practices in each city before landing on one that was right for me. Patient reviews at healthgrades.com may help.

- Certified diabetes educators – are usually (but not always) part of an endocrinology practice and provide help with nutrition, exercise, medication, and medical devices. Some of my best learning has come from caring and knowledgeable nurses and diabetes educators.

Other sources of help include friends with type 1, a select group of diabetes-themed websites, conferences, JDRF connections, and reps for medical device and pharmaceutical companies.

There are times when the demands of managing diabetes are more than we can handle. That means working with professionals with the skills, education, experience, and time for our mental health. It’s a sign of strength when we reach out for this help (I have). Your primary care or endocrinology practice should be able to help with a referral.

*******************